Engaged Learning Briefing

This briefing explores how public engagement can be embedded in university teaching and learning, providing high value educational experiences for students which involve learning in community settings.

What is Engaged Learning?

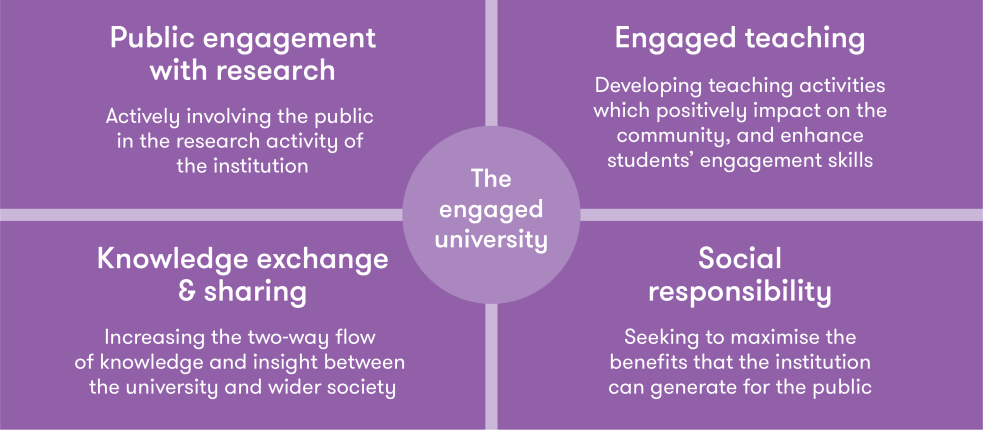

Engagement with the public and with civil society is increasingly animating all areas of university activity, as illustrated in the diagram above. This briefing focuses on the ‘Engaged teaching’ quadrant of the diagram and explores cutting edge and innovative practices in this domain.

Engaged, community-based learning provides a way of generating powerful learning outcomes while also contributing to wider social outcomes. There are many terms used to describe this approach, one of the most widely used being

‘service-learning’ which is defined as follows in Wikipedia:

An educational approach that combines learning objectives with community service to provide a practical, progressive learning experience while meeting societal needs.

The term arose in the US. In the UK, as with the US, various alternative terms exist including community-engaged learning, authentic learning and education for sustainable development. Different terminology exists across different disciplines, including work-based learning, live projects, citizen science, consultancy, co-production, and science communication.

Common across these terms, and the practices they describe, is an emphasis on knowledge as situational and context-driven, interpersonal, and filtered by emotional, cultural and political dimensions. Some examples include:

|

Citizenship The Social Policy MA at the University of Glasgow encourages students to examine aspects of citizenship in relation to education, policy and practice. |

|

Employability and skills The Criminology BA at Nottingham Trent University uses a service-learning methodology, with students working in small groups to apply their criminological thinking and knowledge to real world issues. |

|

Professional practice The planning MA at UCL uses live briefs to develop student capability to address complex professional problems and to develop skills in decision- making under uncertainty. |

|

Building capacity The Science Shop at Queen’s University Belfast provides an open portal for communities to pose research questions to the university. These are then translated into student projects, PhDs, post-docs and other engaged practices. |

Variations in Approach

Service-learning is a useful ‘catch-all’ term for a variety of approaches. These are shaped by the discipline, the different motives and perspectives of staff delivering programmes, the communities involved and their requirements, the nature of the institution, the particular level of study, and the students themselves.

Some of these variations in approach are described below:

|

Dimension |

Key Questions |

|

Traditional vs Critical |

To what extent is the programme focused on issues of social justice? Do students engage with issues of power and privilege? Or is the programme focused more explicitly on developing skills and attributes? (e.g., employability etc.?) |

|

Research on, for and with |

Are students studying or doing research on communities? Is the programme focused on live briefs or providing new knowledge and research for communities? (e.g., evaluations, business plans etc.) Or are students working in partnership with communities and co-producing new knowledge? |

|

Discipline-based, project-based, capstone or dissertation based |

Is service-learning embedded in a course (i.e. as part of a module) or is it available as an elective that all students can take? Is service-learning offered as an alternative dissertation option? |

|

Direct, indirect, advocacy, production, performance |

What will students do with and for communities? To what extent will they apply practical skills in their degree programme? (e.g., planning students doing design work, communications students delivering marketing plans etc.) Or will they be encouraged to develop a broader set of intercultural skills and attributes (e.g., medicine students volunteering to support refugees with the English language)? |

|

Assessment of learning or outcomes |

Will students produce an output for communities? Will this be assessed as part of the learning strategy? Or will the focus be on assessing student learning and reflection? |

Making the case for Engaged Learning

Engaged learning can make a significant contribution to how universities realise social value through research, teaching, knowledge exchange. In particular:

- It enables undergraduate and postgraduate students to learn how to develop positive, mutually beneficial relationships with local communities and organisations - allowing them to fulfil their desire to contribute to social justice while developing their own capabilities and professional skills.

- It can help foster Knowledge Exchange activity, providing consultancy and placements to SMEs, supporting creativity and start-ups, whilst simultaneously helping students develop entrepreneurial mindsets.

- It can connect education and research, enabling students to develop their capabilities as more engaged, connected and empathetic researchers.

- Communities often see it as a core part of their educational mission to support Undergraduate students. At the same time, they may gain access to the resources and knowledge within the University.

- It is a vital way universities and communities can collaborate to bring about social change.

There is a significant amount of excellent practice in this area and potential for this work to be scaled up. Engaged learning seeks to generate the assets that students need to be confident, creative, critical citizens, to be successful in the future labour market, and to develop the attributes that make the world a fairer and more equal place: empathy, compassion, reflectiveness and ethical awareness. To do this the sector will need to facilitate different and more disruptive modes of learning and better align how they realise the potential of teaching, research and knowledge exchange to create social and civic value.

The contribution of Engaged Learning to wider policy agendas

Engaged learning can also help universities and academic colleagues to address the demands of various external stakeholders for new modes of teaching and learning. For example:

- UNESCO’s identification of key competencies for sustainability (systems thinking, anticipatory competency, normative competency, strategic competency, critical thinking, integrated problem solving, self-awareness and collaborative competency) pose significant questions for educators because these abilities are unlikely to be effectively developed in a transmissive or didactic environment. Instead, educators will have to think through experiences and episodes that will help learners to trial, practice and refine such competencies. Engaged learning provides one interesting and productive context where this might be possible.

- Similarly, calls for universities to respond to the need for 21st Century skills (for example, the World Economic Forum’s Education 4.0 agenda) focus on a shift away from academic content and towards developing higher-level capabilities. Again, delivering these through more traditional ‘chalk and talk’ means may prove problematic, akin to trying to teach someone to swim by showing them a video. Finding new ways to engage students in these processes and simultaneously engage them in their subject or discipline will be critical if higher education is to respond positively to these demands.

- In the UK context, the UK Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) has set an expectation that universities articulate the education gain accrued by learners. Providers could include a range of gains, which might include but not be limited to:

- Academic development: such as gains relating to the development of subject knowledge as well as academic skills, for example: critical thinking, analytic reasoning, problem solving, academic writing, and research and referencing skills.

- Personal development: such as gains relating to the development of student resilience, motivation and confidence as well as soft skills, for example: communication, presentation, time management, and networking and interpersonal skills.

- Work readiness: such as gains relating to the development of employability skills, for example: teamworking, commercial awareness, leadership and influencing.

- For individual academic and professional staff, building partnerships and facilitating engaged learning can also be positive components of a portfolio of activity that reflects the principles and dimensions of the UK Advance HE Professional Standards Framework (UKPSF). The increasing emphasis on sustainability in the UKPSF after the review in 2023 again encourages colleagues to consider how best to deliver an education that enables students to develop key competencies in this context.

Taking a strategic approach to Engaged Learning

To seize the potential of engaged learning requires ‘big picture’ thinking and strong leadership. Key strategic challenges which demand attention include:

- Joining the dots between teaching, research and social impact. Prioritising engaged learning can help universities align their strategic priorities for research, teaching and civic engagement. But this requires some disruption of internal ‘silos’. Strong leadership is needed to articulate the vision, join the dots, and target investment of expertise and resource to enable new ways of working to emerge.

- Developing staff and communities. Significant support is needed for both staff and communities. This can come in many forms (e.g. networking, events, workshops, training, scholarships, fellows, awards, pilot or sustained funding etc.). In developing this support, challenging issues need to be addressed:

- Curriculum Design. How to share innovation in learning and teaching and incubate new ideas, building a culture of reflection, development and engaged scholarship? How to design courses that foster connections across subjects and the real world?

- Developing mutually beneficial partnerships. How can engaged learning be framed and delivered around mutual benefits? Where can co-production be deployed effectively? What role is there for students and partners in designing service-learning?

- Assessment. How is student learning best assessed? How should teaching and learning strategies be re-imagined? What support do academics need to move from the ‘sage on the stage’ to enact active learning and facilitate peer groups?

- Equality, diversity and inclusion. What challenges does service-learning surface about equality, diversity and inclusion? How to ensure that placements are fair and accessible to all? How to navigate power imbalances and build power in communities? What steps are needed to de-colonise the curriculum?

- Capacity building. Engaged learning typically requires different resources than those required by traditional forms of teaching. Furthermore, academics seeking to pilot approaches often need more support to get started. Moreover, universities must build capacity in community partners and networks to work with students. Resources in the form of staff, pilot funding and for training and development need to be considered.

- Evaluation and impact. What evaluation frameworks are needed to measure impact and support the development of student and community outcomes? How can we effectively assess the value of this work? What role do policy instruments of quality assurance and teaching excellence play?

How to embed support for engaged learning

Embedding support for service-learning is a complex strategic challenge. Just bolting on some ‘experiential learning’ modules fails to get close to realising the potential of this approach. However, making the move from tinkering with the curriculum towards developing an embedded, strategic approach is very demanding and asks big questions of a university.

Some useful questions to address with colleagues, students and partners include:

- How can universities exploit the teaching and research nexus productively?

- How can courses and programmes help students advance their capabilities and competencies through experiential learning? How can we use the institution’s assets, or the resources on the doorstep, to create meaningful and purposeful experiences?

- How do universities build students’ sense of purpose and agency in their studies? How can engaged learning build a sense of belonging and identity with the discipline, the University and its surrounding communities?

- To what extent can civic engagement, service, volunteering or leadership contribute to staff and student well-being?

- How might universities support communities to implement some of the positive outcomes/new knowledge they co-create with students?

- How should universities respond to the challenges that Artificial Intelligence brings to traditional delivery and assessment modes? Are there other forms of learning that are more authentic and personalised which can step around (or be antidotes) to plagiarism and other apparently 'unfair' means?

These are challenging and complex issues to unpick. But many students want to be more than consumers of knowledge. They wish to find ways to apply their knowledge, have agency, and ‘make a difference’. They demand different modes of learning.

Done well, engaged learning brings the discipline or subject area to life in a way that challenges more traditional approaches and objectives. It's not just the practical application of knowledge to real-world contexts: it’s a way of learning that can bring intrinsic motivation and heightened engagement, though one that may only be suited to some learners and contexts.