Exploring the Wheel of Consent in Participatory Research

Delegates at the Engage Conference 2024 may remember Bramble Gardiner's workshop exploring the roles and interpersonal dynamics in participatory research.

In this blog, Bramble shares insights from that work and their PhD, including a new framework designed to support reflection in ethical participatory processes.

From community practice to academia

I began my career as a community artist, later working in the third sector on community-engaged projects like citizen science. When I started my PhD in 2022 and transitioned into academic participation, I noticed how bureaucracy slowed things down (Figure 1) and reduced flexibility in responding to participants.

In the third sector, the focus is often on immediate action and outcomes for communities. In contrast, academia tends to prioritise publishing and long-term influence. While some academic projects aim to include immediate action, it’s often difficult to make this a central priority.

Figure 1: Having previously worked in the third sector, adjusting to the slower pace of academia was challenging. Image by Bramble Gardiner (2023), part of ‘The Comic Life of a PhD Student’.

Introducing the ILBR Framework

While reflecting on these differences and engaging with literature on participatory research and co-production, I recognised parallels with the ‘Wheel of Consent’ - a framework that explores dynamics of taking, allowing, giving, and receiving.

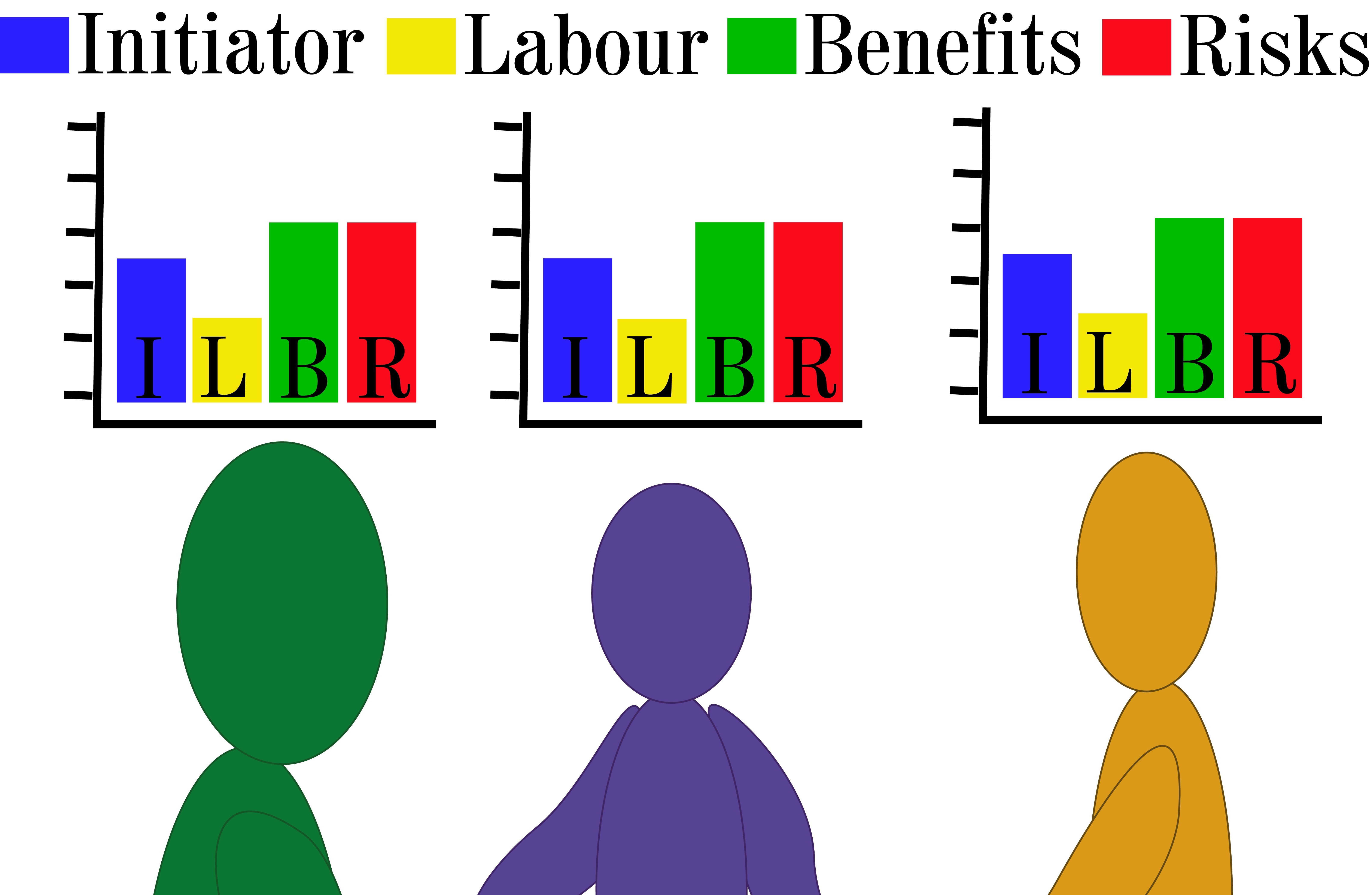

This led to the development of the ILBR Framework, which centres four key questions:

- Initiating: Who is making requests or offers, and to whom?

- Labour: Who is doing the work or taking the action?

- Benefits: Who is the work or action for?

- Risks: What risks exist, and for whom?

The framework encourages reflection on whether these elements are equitably distributed among all participants. Equity doesn’t mean equal amounts for everyone - context matters. Participatory processes often involve evolving dynamics over time, so it’s helpful to consider balance across the project’s duration.

It’s also important to reflect on social positions, power, and inequality. For example, habitual practices may mean certain people are always consulted but rarely lead. This can reinforce existing power dynamics.

As an example, academic researchers often initiate participatory processes, do most of the labour, take on risks, and receive many of the benefits. However, long-term collaborators also contribute significant labour and take on risks. Ensuring a fair distribution of benefits - and understanding what participants value - is essential. Creating space for all collaborators to make requests or offers can help shift entrenched dynamics. Making the balance of requests, labour, benefits, and risks transparent can also spark useful conversations.

Figure 2: Each person in a participatory process contributes varying levels of labour, benefits, risks, and initiation. This visual invites reflection on how these elements are balanced in practice. Image by Bramble Gardiner (2025).

Using role play to shift thinking

The ILBR framework was shaped by input from many people, including Betty Martin (creator of the Wheel of Consent) and Rupert Alison. A key part of its development was a role-play workshop where participants explored ILBR questions by adopting fictional roles - funder, researcher, university, community partner, and participant.

This workshop was delivered at several conferences, including NCCPE’s Engage Conference 2024, and helped refine the framework. Many participants said it sparked new insights.

Institutional processes can be barriers to genuine participation - a point highlighted by the Co-Production Futures Inquiry. Educational role-play has long been used in teaching, supporting safe exploration of possible actions, role conflicts and the perspectives of others. Our experience suggests it also can disrupt habitual thinking and open space for innovation in participatory research and practice.

Next steps

I’m keen to collaborate with others, whether to run the workshop, adapt the framework for different settings, or hear how it’s being used. This feels like the beginning of a journey, and I’m excited to see where it leads.

Importantly, this blog isn’t suggesting the third sector always does participation better than academia. In my third sector roles, I was sometimes ‘parachuted in’, which had mixed outcomes. Third sector projects also face constraints, like needing to pre-define activities for funding, which can limit responsiveness. So, the ILBR questions may be relevant across sectors - especially when considering how often those being ‘helped’ get to make requests for what they actually want.

Get in touch with Bramble - bramble.gardiner@plymouth.ac.uk

Acknowledgments

This research was part of a PhD funded by the University of Plymouth. Supervisors and co-authors: Dr Clare Pettinger, Dr Louise Hunt, Professor Mary Hickson. Thanks to everyone who contributed to the development of ILBR and the workshop.